As the plane dips it’s wings and drops below the densely-wooded ridgeline the sound of a lilting flute fills the cabin. It turns what could be a nervy experience, into something almost spiritual - only mildly spoilt by the screaming baby a few seats away. From the window, clusters of white prayer flags and green-roofed farms can be spied clinging to the steep slopes, as we follow the contours of the valley and make our final descent into Paro International Airport.

It’s the first sign that Bhutan looks at the world a little differently than most countries. The land of the Thunder Dragon, also known as the happiest place in the world, certainly turns out to be very different to anywhere else I have been fortunate enough to travel.

It is a country I have wanted to visit for over twenty years - ever since a chance conversation with a doctor around a campfire in a remote corner of Tanzania. That desire has since been fuelled by countless conversations with travel writers and photographers who have all been quick to sing the praises of this landlocked state firmly wedged into the Himalayan foothills between Nepal, India and China.

High expectations indeed, but expectations, I am happy to say Bhutan meets with ease. Yet often in ways I didn’t expect. It’s a land of verdant cypress forests, ornately decorated farmhouses, crystal-blue mountain streams, and fairy-tale fortresses that stand guard over bucolic valleys carpeted a golden yellow with ripening rice.

Land of spirits

But is also so much more than spectacular vistas. It’s a country where spirituality seeps into all aspects of life. From the daily mantras intoned by our guide Sonam to welcome the day, to the thousands of miniature tsatsas (votive offerings), coloured conical sculptures that can be found huddled together in their hundreds at every scenic spot, cliffside overhang or temple windowsill.

This is a land deeply imbued with religion, most clearly evidenced by the prayer flags slung across roads, bridges and between trees, their fluttering panels of blue, yellow, red, green and white cloth sending messages of goodwill and compassion out across the countryside.

Our four night, five day trip was too short to fully grasp the many joys of this small but fascinating country, but it was long enough to experience some of Bhutan’s more famous highlights: the vertiginous monument to what religion can achieve that is Taktsang Monastery (better known as Tiger’s Nest), the brooding fortress of Punakha Dzong, the cloud-coated stupas of Dochula Pass and the gorgeous Gangtey Valley.

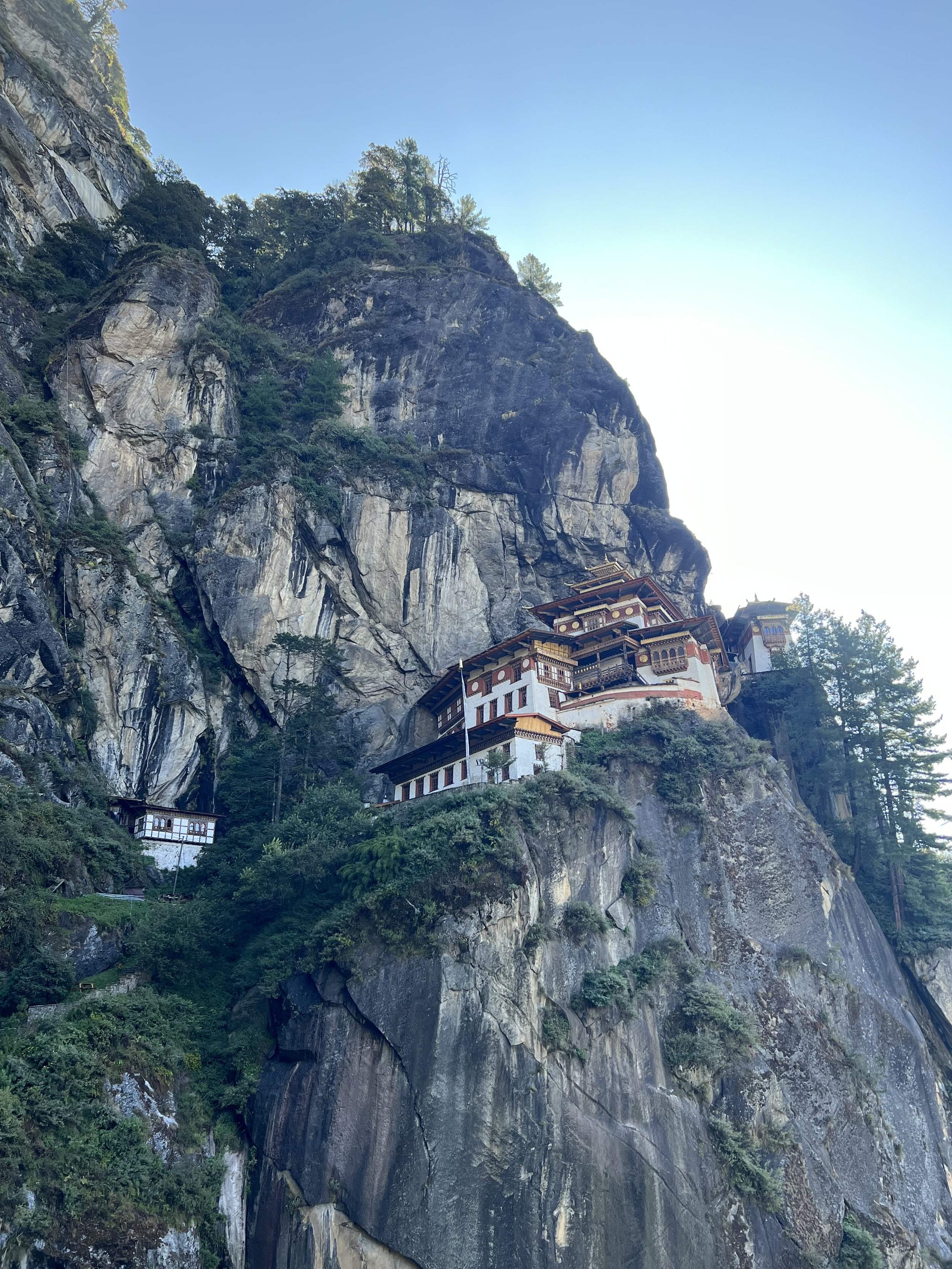

Tiger’s Nest

All were memorable in their own ways. The hike to Tiger’s Nest which sits at over 3000 meters is both exhausting due to the altitude, but magical thanks to the surroundings – the views over Paro valley and up to the cliffside temple complex truly breath-taking. The effort to reach the shrine, which was built in dedication to Guru Padmasambhava, the initiator of Buddhism in Bhutan, simply underlines the crazy effort of reverence needed to construct the original buildings way back in the 16th century.

As we huffed and puffed our way up the well-worn track we were greeted by the chirrups and whirrs of the babblers, bulbuls, flycatchers and minivets that inhabit the surrounding forests, and received a boisterous welcome from the pack of local dogs that live on the mountainside. One in particular dubbed Michu by Sonam, seemed to lead us along the sun dappled track, rushing ahead only to look back and wait for us to follow. He only left us once we had ascended to the thousand-foot waterfall that marks the entrance to the temple, trotting off without a care in the world, content that his day’s work was done.

The temple complex which teeters on the edge of the vertical cliff face, is small but dripping with atmosphere. Our experience is heightened by the fact we are also the first tourists to arrive. This delights Sonam, who has made this trek over twenty times but never reached the top first before. His delight is clear later on as he gleefully greets his fellow guides still heading up with their tourist groups as we (slightly smugly) make our way back down.

The resident monk, bespectacled and clad in the traditional orange and red robes tells Sonam that our efforts to get here first grant us the honour of lighting the votive butter candles in the main shrine. In the cramped space, ceiling coated in soot, walls covered in coloured murals, a statue of Guru Padmasambhava as a demon, riding a ferocious tiger (one of his wives) reflects the guttering candle light as the monk proceeds to prostrate himself and chant a morning invocation.

Even the bin men have a unique style in Bhutan

It's pretty magical moment, ironically made more memorable by the fact that we’ve had to leave our phones and cameras with security at the temple entrance. There’s nothing for it but to just live the experience. We are then blessed with a further twenty minutes exploring the different chambers and shrines before any other tourists arrive. Low-ceilinged, crammed with golden statues and smoky with candles the whole place exudes a sense of sombre, weighty religiosity.

To have such a famous destination all to ourselves, even for a short time, is very special. Of course timing, luck and the season all play their part, but it is also a reminder of how carefully managed tourism is in Bhutan. The country applies a daily tourist tax to every visitor and limits annual visitor numbers to around 300,000 individuals a year, as a guide neighbouring Nepal has around one million. Our experience is definitely richer for it as we feel like we’ve been given VIP access to the best of Bhutan without having to battle the crowds.

The valley view from our guesthouse

Punakha Valley

We have the same experience at another major landmark, the 17th century fortress Dzong Punakha. Located in the heart of the Punakha Valley, the second oldest and the largest citadel in Bhutan sits resolute at the confluence of two fast flowing rivers. With its thick white walls and elaborately carved wooden towers, topped with red and gold roofs it is both ethereal and imposing.

It looks particularly enchanting at night, a sight we get to experience from Dharma Siddi, our charming two story guesthouse, perched on a slope looking down onto the valley. As dusk draws in and the temperature drops, we find it hard to drag ourselves away from the veranda as the fort glints and shimmers below us.

Next morning, we woke to the sound of birds and a view concealed in mist. After a breakfast spent watching the cloud slowly lift to reveal the fort, we head back down for a closer view and are again the first tourists to arrive. The Dzong’s entrance is via a covered, cantilevered wooden bridge over the Mo Chu River. First constructed back in the 17th Century, though rebuilt in the early 2000s, the crossing feels like a portal backwards in time. The dream-like mood is heightened by a dog sprawled motionless in the morning sun and a craggy monk sat at the end of the bridge worrying away at his prayer beads.

The fort, both serene and spectacular, features a series of courtyards which are accessed by an imposing staircase. The giant wooden door flanked by two giant gold prayer wheels and vibrant murals. Still a major administrative centre, civil servants in the national dress of oversized knee-length jacket, a kabney (silk scarf) slung over the top and knee length socks, bustle about the first courtyard, which is dominated by a magnificent bodhi tree, guarded by a proud rooster.

As we head further in, it’s hard not to be overwhelmed by the flamboyance of the decorative efforts, every window sill, pillar and door frame enlivened by colourful murals and intricate carvings. And aside from two other small groups it’s almost empty of tourists. Instead we rub shoulders with a few local devotee, come to this important religious site to pay their respects.

We are also treated to a chance sighting of Jigme Chodra, the most senior religious figure in Bhutan. The current Je Khenpo or Chief Abbot is here to pray to Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal, recognised as the original unifier of Bhutan, whose remains are kept in a temple in the inner courtyard.

The hushed excitement that greets his presence is a reminder of religion’s central and active role in daily life. It’s clearly a treat for our guide Sangsom, who excitedly texts his family to share news of this fortuitous encounter. Yet, it’s also wonderfully low key. There is little fanfare and low security for the rotund but stately monk who only has a couple of colleagues in attendance as he ambles across the courtyard and disappears inside the off-limits temple.

Food for thought

While I had perhaps expected such spiritual encounters, I hadn’t expected the food to be such a revelation in Bhutan. I had imagined heavy stews and hearty curries would dominate, but this proves far from the reality.

An evening meal of vegetarian delights at Dharma Siddi in the Punakha Valley

Ourt culinary highlight is unquestionably a spectacular evening meal we enjoyed on our first night in Punakha Valley. Prepared by the three young women who ran our guesthouse, we were treated to a selection of vegetarian dishes featuring ingredients plucked fresh from the on-site garden. Mushrooms with bean sprouts, fiddlehead and cheese, cucumber with paprika, peppercorn and cheese and spinach and crispy potato. Each is simple and rustic, but also delicate and bursting with flavour. And aside from a divinely unctuous dish of chili chicken with broccoli, it’s a meal that makes it easy to imagine going vegetarian.

Something I hadn’t considered before arriving was the fact that they grow the large majority of their own produce. What’s more their strict adherence to Buddhist principles means most people eat little or no meat. In fact, there are no slaughterhouses in Bhutan, with any meat brought in from India. Hunting and fishing are also illegal – though ironically fishing is a tourist draw in Bhutan you just have to release any fish you catch.

Simon modelling the power of Druk 11000

The majority of our meals are restricted to tourist buffets, evidence of the focus on small group travel, even if we did yearn to try some of the rickety roadside lean to shacks that doubled restaurants. While not exactly thrilling are always tasty, fresh and filling, typically consisting of a few vegetarian dishes, red and a bowl of rice and chili cheese – a local delicacy that is pretty much as it sounds. We did also get to go more local when we pay a visit to Momo House in Thimpu. This unpretentious dumpling (momo) spot is as close to fast food eating as we get in Bhutan.

We do also stop by the Namgay Artisanal Brewery in Paro to enjoy some intriguing craft beers, enjoyed while overlooking a match from the Bhutanese Premier League – football is big here with the King a massive fan. But the tasty craft beers on offer are no match for another stand out Bhutanese discovery, Druk 11000. The wonderfully named local beer of choice is a punchy 8% lager made from fresh Himalayan mountain water. Not only is it cheap and delicious but it has the magical ability to turn my travelling companion, Simon and I into giggling fools about three minutes after drinking it. Unfortunately, it has proved insanely expensive to procure in Singapore but if anyone knows where to get hold of some…

Our home stay in Gangtey Valley

Gangtey Valley

A lot less enjoyable, though also memorable, was the bowl of hot, soupy and sour homemade rice wine we sampled during our homestay in the beautiful Gangtey Valley. This u-shaped glacial valley in Central Bhutan, is a fertile, marshy place that’s home to stupas, water prayer wheels, and traditional Bhutanese farmsteads along with wild flowers and woodland. Come at the right time of year (late October to mid-February) and you may even get to hear the distinctive honking cry of the black necked cranes who head here from Tibet in the winter months.

Their arrival is seen as auspicious, and is celebrated with an annual dance festival at the Gangtey Monastery, which sits at the head of the valley. The monastery also marks the starting point for a wonderful two hour walk down to the crane visitor centre located in the valley floor. The route takes us via alpine pastures, pine scented trails and dusty gravel tracks where we are forced to step aside to make way for a brightly painted lorry to bounce past piled high with potatoes, for which the area is well known.

Walking through a high altitude forest, trees coated by moss, branches bedecked in long strands of seaweed-like lichen I find myself shaking my head at the beauty of it all. It feels as if have stepped into a scene from Lord of the Rings. It wouldn’t have been a surprise to see a troll wander by or for one of the trees to try and engage me in conversation. Instead greetings come in the form of the clanging water-driven prayer wheels the mournful ravens, inquisitive long tailed blue magpies and vivid blue whistling thrushes that dart between the trees.

The natural world is never far away in Bhutan which is one of just a handful of Net Zero countries thanks to their reliance on hydropower and a concerted effort to protect their natural spaces. Over 70% of its land remains under forest cover home to red pandas, binturongs, sloth bears and a thriving population of tigers.

The Valley boasts a preponderance of year-round bird species that include Snow Pigeons, White Wagtails and Yellow Billed Choughs, but it’s the visiting cranes that are the main reason the region was designated a Ramsar protected wetland site in 2016.

During their stay here, they get to share the soggy marshland with indolent cows, herds of shaggy horses and, apparently, the occasional leopard. Indeed concerns over the presence of the big cats are evident in the high stone walls that surround the individual farms and the sight of the local horses being corralled together for safety overnight.

Situated at over 2000m, the gentle slopes of the valley are often shrouded in mist and cloud and while spectacular it must also be a harsh and challenging place to stay in winter. It was chilly enough in October when we spent a night in a home stay, situated on the edge of a small settlement strung out along a babbling stream. We were certainly thankful for the welcome of our hosts, along with the wood burning stove and salty butter tea to keep us warm. The two story wooden home was a basic but cosy bolthole, where after a walk to meet the local kids and cows,we spent a surreal night playing dog top trumps and rummy with our guide while our driver, a former ex-monk, chanted mantras in the next door bedroom.

Changing nation

Despite the idyllic views life here is clearly tough. The owner of our homestay explained how he has been a farmer, tour guide and carpenter just to try and make a living and give his children the opportunities he didn’t have. All of them got a good education and now live in Thimpu and Paro. He admitted that they have little interest in taking over the remote farm in the future.

It seems that this is a reality across much of the country. The internet and TV, which arrived in the 1990s are beginning to have an impact on Bhutan’s fiercely protected culture and accompanying traditions. The country is also a victim of its own success. The younger generation benefit from free schooling, which takes place in a mix of Dzongkha (the national language) and English. But education means that many opt for careers in the capital Thimphu, or even beyond Bhutan’s borders, rather than settle for a difficult life as a farmer in one of the country’s fertile but isolated valleys.

Thimpu

As an outsider it can be hard to see the appeal of Thimpu. Wedged into a steep sided valley, the city is quite a scruffy, chaotic affair thanks to its dusty pot holed lined roads, preponderance of half-finished building sites, and tired-looking low rise apartment blocks. Still as with any capital, it has its own charms, from the dramatic golden buddha that watches over the city to the charming absence of any global brand names or chains on what counts for the main street.

And it’s probably the only capital I’ve visited where you can go and watch a group of locals practice their archery skills on a scrappy patch of land in the middle of the city. It’s like watching a group of guys down the pub playing pool, except they are shooting bamboo arrows 145m towards a tiny target, which I can’t even see with the naked eye.

Arrows and hot baths

We do get our own try at archery later in our stay, though at about a third of the dizzying distance. We also demonstrate about a third of the accuracy at both the archery and the other local game of Khuru, which is basically involves throwing oversized darts at the same target.

These experiences follow a traditional hot stone bath, enjoyed in what looks like an old stable block in a chilly farm compound on the edge of Paro. The bath is something of a trial as we try and bring ourselves to step into the scalding water, sprinkled with medicinal herbs. It’s meant to be health giving but it feels more like a form of medieval torture. That feeling is not helped by the over-zealous bath attendant. With teeth stained red by betel nut, there’s an almost sadistic glee in his cries of ‘more heat, more heat’ as he attempts to add more red-hot stones to the already blistering bath water.

Standing naked but for a towel in a chilly stone shed, willing each other to take the plunge is a surreal but unforgettable moment. And there are simply way too many of those to include here. Chance roadside encounters with golden langurs and yellow-throated martens. Distant views of the Himalayan foothills spied from mountain passes. Ancient suspension bridges garlanded with prayer flags strung across raging torrents. Houses painted in giant mythical creatures and priapic phalluses (a positive sign of fertility). And then there are the endless vistas of tumbling waterfalls, golden rice fields, mountain streams and the forested hills dotted with prayer flags, farmsteads and monasteries.

Bhutan is a truly bewitching and breath-taking country and one that was definitely worth the wait. I just hope it’s not another twenty years before I get to return.

Special thanks to Simon for some of these pictures, being a great travel companion and for starting the drunken conversation that inspired us to go in the first place!